by Essity, manufacturers of the Cutimed® wound management range

Traumatic open wounds are a common occurrence all year round for veterinary professionals, but as the weather improves with the summer months, pet owners and their animals will be venturing out on more adventures in nature. It is during this time of year we may start to notice a rise in certain traumatic wounds; stick injuries, lacerations caused by unknown foreign objects, and bite wounds.

Management of open wounds should ideally follow a systematic and holistic approach, that incorporates evidence-based basic wound management techniques, which together should improve healing outcomes and minimise complications.

Factors that cause wound healing delays

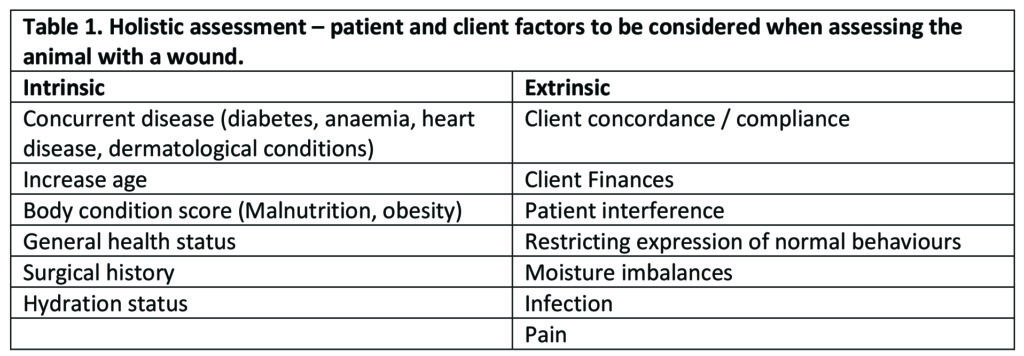

When presented with an open wound it can be easy to become distracted by the large open deficit in front of us but stepping back and viewing the bigger picture can help to shift attention to a patient/client-centric focus when creating a wound management plan. The basis of a wound management plan should include an assessment of extrinsic and intrinsic factors that could delay wound healing (See Table 1 below)

Certain factors can be mitigated or eliminated, but others can be more challenging. Successful client concordance relies on effective communication and education of pet owners.

Concordance differs from the more traditional idea of client compliance in that a treatment plan is created based on shared decision-making between the veterinary professional and the pet owner1.

Client compliance, which is a term more of us may be more familiar with, is the pet owner’s agreement to adhere to a treatment plan that has been outlined to them1. Where we would expect client compliance in wound care is around bandage care, if the client does not follow a set of instructions it could end in complications for the animal in the form of bandaging injuries.

So, we must look at how we can merge these two concepts to try and maximise outcomes. The use of a holistic wound assessment and getting the pet owner on board with the idea that the wound-healing process is dynamic and may need to be altered at different stages2. Pair this with setting small step goals that are re-assessed at each presentation of the animal can aid in helping to improve client compliance and concordance. Once factors that may affect wound healing have been established, a full wound assessment can be performed, followed by wound bed preparation and placement of an appropriate dressing.

The utilisation of a standardised wound assessment framework, such as T.I.M.E.S (Figure 1, below), can help to identify certain clinical observations seen within the wound bed and surrounding skin and how we can correctively manage certain aspects to maximise wound bed preparation, which promotes healing and improved patient outcomes3.

Figure 1. T.I.M.E.S acronym highlighting 5 clinical observations that require management in the wound bed to maximise healing outcomes. Tissue type, inflammation vs infection, moisture balance, edge of wound and surrounding skin.

T: Tissue type & management

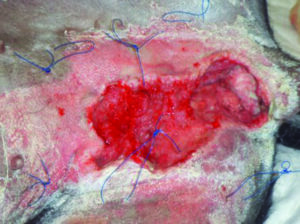

Determine if there is viable or non-viable tissue present within the wound bed. Presence of nonviable or deficient tissue (slough/necrosis /eschar Figure 2a ) can all potentially impact healing4.

Non-viable provides a focus microbial replication leading to wound infection, it can prolong the inflammatory response, and mechanically obstruct contraction and impede re-epithelialisation4.

Debridement is the most appropriate way to manage non-viable tissue, the type of debridement should be based on what is most appropriate for the individual case3. If tissue is viable, granulation tissue (Figure 2b), ensure to support the moist wound environment using a hydrogel, such as Cutimed® gel.

Figure 2a. tissue necrosis and eschar at surgical site dehiscence on canine lateral thorax

Figure 2b. Viable tissue, granulating wound on feline lateral thorax

I: Control Inflammation and infection

Inflammatory exudate is released naturally during the first phase of healing and makes up part of the body’s wound-cleansing process. We mustn’t confuse normal inflammatory signs to be signs of wound infection. There are a few key clinical observations we are looking out for to differentiate between the two.

In normal inflammatory signs, we should see these peak at approximately day 3 and during this time proliferation will begin. Viable tissue should be created simultaneously while the body is wound cleansing and managing bioburden. Bear in mind that every wound is going to have a degree of contamination so keeping this at a level where the body can handle microbes itself is important.

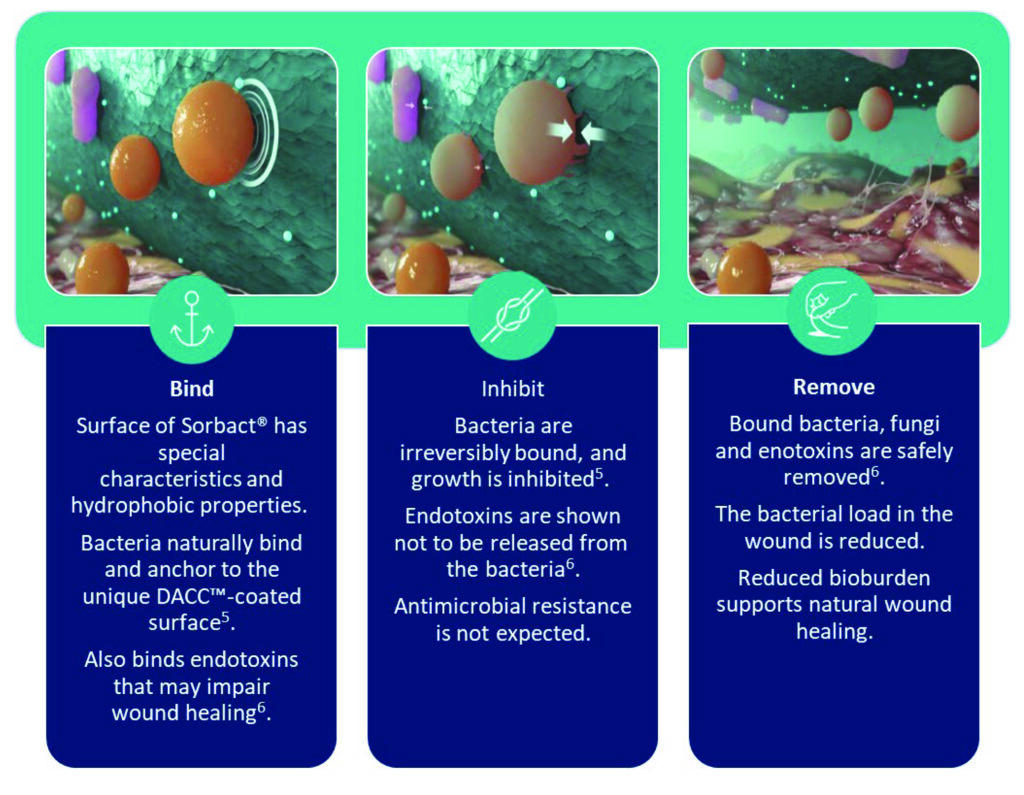

Consider the use of alternative topical products that work through a physical mode of action rather than reliance on systemic antibiotics to try to combat antimicrobial resistance. Cutimed® Sorbact® works through a physical mode of action to bind, inhibit, and remove bioburden when placed in direct contact with the wound bed5. This is then removed when the dressing is changed effectively minimising bioburden and aiding to potentially lower the requirement for systemic antibiotics7 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Physical mode of action of Cutimed® Sorbact®

Because of the physical mode of action, Cutimed® Sorbact® can be used prophylactically or during active wound infection to inhibit the growth of common wound pathogens5, including Methicillin Resistance Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) and Vancomycin Resistance Enterococci (VRE)8, and as it is non-cytotoxic and does not release active agents into the wound bed it facilitates the normal wound healing process9. (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Cutimed® Sorbact® mesh packed into wound on a turtle post head injury.

M: Moisture imbalances

We have discussed how inflammatory exudate is produced as part of the body’s natural inflammatory response, but the level of exudate produced can depend on pressure gradients applied to the affected tissue10.

Increases in movement, friction, and pressure can lead to imbalances of moisture within the wound bed, the body will under normal circumstances produce enough fluid to promote cell proliferation and autolysis within the wound bed10.

If our exudate production is not managed or other factors lead to increases in exudate incorrect management can lead to chronic wound healing and increased risk of wound infection and moisture-related injuries, for example, maceration of the surrounding skin10 (Figure 5).

Application of moisture balancing dressing or use of sub-atmospheric electronic pumps, such as vacuum-assisted compression (VAC) or negative-pressure wound therapies, can aid in managing moisture imbalances.

Figure 5. Maceration of surrounding skin due to tissue damage. Photo copyright: Elisa J Best BVSc Cert SAS MRCVS RCVS advanced practitioner in small animal surgery.

E: Edge – advancing the epithelial wound edge

Wounds contract from the circumferential edges’ inwards, the body will choose the path of least resistance when epithelising. For a wound to epithelialize several factors need to be present for this to take place, a well-vascularised granulation bed for cells to migrate over that also provides a good oxygen supply and nutrients to support tissue regeneration10.

If the cells are not supported, they slow down and lose functionality. Where we see non-advancement from the edge of the wound is usually due to poor quality cell proliferation, cellular DNA damage or prolonged inactivity of the cells from desiccation of the wound bed.

The simplest method of supporting and maintaining cell functionality is to promote a moist wound-healing environment10.

S: Supporting Surrounding skin

The surrounding skin should be monitored, and the skin’s integrity maintained. Prolonged exposure of fluid on intact skin can lead to peri-wound moisture-associated skin damage, and wound exudate that contaminates the peri-wound area for prolonged periods of time can lead to skin damage. This causes inflammatory response and erythema and can be seen with or without erosions11.

Protecting the surrounding skin using an appropriate medical skin barrier product can help prevent moisture-associated skin damage.

Cutimed® PROTECT cream moisturises the skin preventing it from dying out while maintaining permeability to water vapour and oxygen (Figure 6). As a preventative Cutimed® PROTECT barrier spray can protect intact skin from irritation caused by friction and maintain its barrier function for up to 96hours12.

Figure 6. Barrier cream applied to circumference of wound to prevent and manage moisture associated skin damage during wound care.

Summary

Performing effective wound management requires more than just being able to assess the visual observations seen within the wound bed. A solid understanding of cellular aspects of the healing process can aid in ensuring that as veterinary practitioners we understand why we may be using a type of wound management technique.

Performing a holistic assessment and re-assessment at each dressing change using a standardised framework such as T.I.M.E.S and conducting appropriate wound bed preparation that maximises the wound healing processes can improve patient outcomes and client satisfaction.

References:

- Little, G. (2013). ‘Concordance and compliance’. Improve Veterinary Practice: InFocus. [Online] CONCORDANCE AND COMPLIANCE – Veterinary Practice

- Hall, J. (2023). ‘Wound care in companion animals’. Vet Time Podcast. Soundcloud [Podcast] Jan 2023.

- Vera, M., (2016). ‘Wound bed preparation and beyond’. Wound Source. [Online] The Principles of Wound Bed Preparation and TIME

- Baharestani M. (1999). ‘The clinical relevance of debridement’. In: Baharestani M, Gottrup F, Holstein P, Vanscheidt W editor(s). The clinical relevance of debridement. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1-15

- Husmark, J., Morgner, B., Susilo, Y. B., & Wiegand, C. (2022). Antimicrobial effects of bacterial binding to a dialkylcarbamoyl chloride-coated wound dressing: an in vitro study. Journal of wound care, 31(7), 560–570.

- Susilo, Y. B., Mattsby-Baltzer, I., Arvidsson, A., & Husmark, J. (2022). Significant and rapid reduction of free endotoxin using a dialkylcarbamoyl chloride-coated wound dressing. Journal of wound care, 31(6), 502–509.

- Chadwick, P., & Ousey, K. (2019). Bacterial-binding dressings in the management of wound healing and infection prevention: a narrative review. Journal of wound care, 28(6), 370–382.

- Ronner, A. C., Curtin, J., Karami, N., & Ronner, U. (2014). Adhesion of meticillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus to DACC-coated dressings. Journal of wound care, 23(10), 484–488.

- Morgner, B., Husmark, J., Arvidsson, A., & Wiegand, C. (2022). Effect of a DACCcoated dressing on keratinocytes and fibroblasts in wound healing using an in vitro scratch model. Journal of materials science. Materials in medicine, 33(2), 22.

- Dowsett, Caroline & Newton, Heather. (2005). Wound bed preparation: TIME in practice. Wounds UK. 1.

- Essity, (2014). ‘Cutimed® PROTECT: the skin barrier with proven efficacy’. BSN Medical UK.

The article was originally posted in The Cube magazine, June 2024 issue. Click here to read the magazine.