by Essity

Mud fever, sometimes called pastern dermatitis or rain scald, is frequently seen in horses during wet seasons when there are muddy conditions, but is not isolated to certain times of the year. Pastern dermatitis causes a skin irritation to the horse’s lower limbs, such as the pastern or heel, that causes lesions and inflammation which may be painful and itchy¹. Any breed of horse, donkey or pony may be affected by pastern dermatitis, but certain breeds may have a disposition for the condition, such as those with feathering. Rain scald typically affects the abdomen or back of the horse and is linked to wet conditions or over-rugging leading to excessive sweating¹.

Aetiology and Pathogenesis

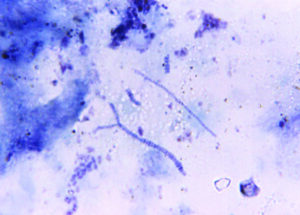

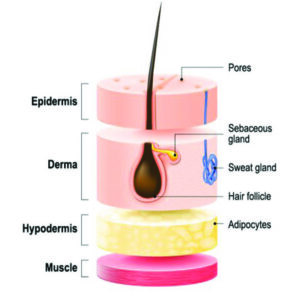

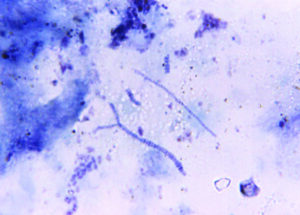

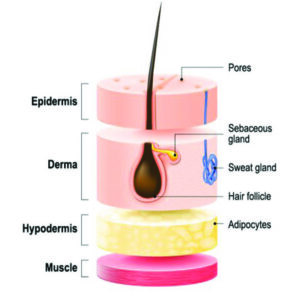

There is no one single cause for Mud fever and as with most conditions, the cause can be multifactorial. Most literature suggests an underlying contributing factor is the chronic exposure to wet conditions where exposure to a non-contagious gram-positive bacterium; Dermatophilosis Congolensis².(Figure 1). The bacterium replicates in moist warm environments but its natural habitat is unknown, attempts have been made to isolate it from soil samples, but this has been proven to be unsuccessful and it is more likely spread via direct contact between affected or asymptomatic animals, from contaminated environments or via biting insets². If exposure occurs the bacterium is isolated within the living epidermal layers (Figure 2) whereupon replication it will cause an acute inflammatory reaction of the skin². For localised skin infection to develop specific climatic conditions are required; the bacterial spores are activated by wet or moist conditions and when paired with poor skin integrity, pre-existing wound or an immunocompromised horse, replication of the bacteria within the epidermis or wound will become uncontrolled leading to an established infection².

Figure 1: Dermatophilosis Congolensis morphology, showing filamentous hyphae and motile zoospores, under Giemsa-strained photomicrography

Figure 2: Structure of the skin showing the epidermis where Dermatophilosis Congolensis replication can take place in the horse.

Extrinsic factors can contribute to the development of mud fever. If the horse is over-exposed to moist or wet conditions moisture-associated skin damage (MASD) can occur, where the skin is softened increasing the risk for breakdown in the skin’s barrier, another cause for this may be over rugging where the horse excessively sweats leading to MASD¹. Poor environmental hygiene where the horse is stabled in dirty bedding.

Intrinsic factors include a genetic predisposition, thoroughbreds or Arabs have thinner skin which can be damaged more easily, and horses with white markings or limbs which is more sensitive than pigmented skin or darker hair. Mud fever can also be secondary to other disease processes; pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) or Equine Cushing’ Disease, which causes hormonal dysregulation and any condition where the horse’s immune response is affected¹.

Signs and symptoms

Mud fever tends to cause overt signs of inflammation and infection, figure 3 shows the common presentation of mud fever. Some of the most common signs, but are not exclusive to:

- Eschar (sacbs) formation

- Damage to skin integrity

- Alopecia with excoriation

- Matted hair

- Lesions that exudate purulent discharge

- Localised inflammation (erythema/swelling)

- Mild pain (more so if infection)

If this condition is left untreated cellulitis or lymphangitis can develop (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Lesion in equine limb with mud fever (Image credit: Northland Veterinary Group)

Figure 4: Cellulitis in equine limb, showing signs of severe swelling

Diagnosis

A full holistic assessment of the horse should be carried out, this will include checking for mites and assessing other horses in the yard for signs and symptoms. Diagnosis can be made on clinical signs and assessment, further tissue samples may be taken such as acetate tape impressions, skin scraps, or swabs to look for fungal or bacterial infections. If the problem is not responding or there is suspicious of a neoplastic (tumor or sarcoid) lesion, immune-mediated condition (pastern and cannon leukocytoclastic vasculitis or pemphigus foliaceous) then full-thickness skin biopsy may be sent off for histopathology where the structure of the skin cells and layers will be examined under a microscope by a specialist.

Treatment

Treatment may vary depending on the cause behind the mud fever. A multimodal approach is usually required, and the aim is to treat any underlying condition and repair the skin integrity. Considering the environment the horse is being kept in, stabling may be necessary to remove the wet-to-dry cycle, turnout in an arena may be an option if the conditions are dry, but care should be taken if sand is present as this can cause further irritation to the damaged skin. This is important in horses with an established infection and the horse should be kept out of the mud and wet conditions until clinical signs have resolved.

Feathered horses will benefit from having their legs clipped. This allows not only visualisation of the affected area but also permits the hair and skin surrounding to dry quicker and for topical treatments to be more effective at reaching the targeted area¹.

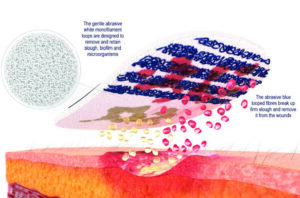

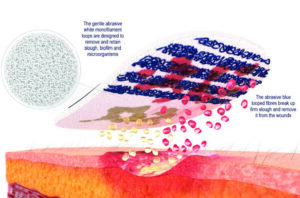

The lesions should be gently soaked and removed, this can be done using non-cytotoxic antiseptic solutions or isotonic solutions warmed to body temperature and paired with a debridement pad². Cutimed® DebriClean is a debridement pad that consists of monofilament microfiber loops that cleanse and debride superficial wounds and the surrounding skin (Figure 5). This method should be atraumatic for the horse but consider the use of appropriate analgesia based on signs of pain. The limbs should be thoroughly dried after cleansing to prevent further moisture-associated skin damage.

Other treatments can be prescribed on a case-by-case basis:

- Bioburden reduction using dressings that work by a physical mode of action, such as Cutimed® Sorbact®, a bacterial binding dressing that can be applied under stable bandages if being used.

- Use judicial use of systemic antibiotics should be considered and their use based on systemic signs and symptoms within the horse and paired with culture and sensitivity testing.

- Appropriate analgesia used based on pain assessment of the horse¹.

- If mud fever is secondary to a mite infestation, then this will need to be treated to prevent chronic itching that further damages the skin barrier.

- Stabling during the day or using ultraviolet, turnout socks for horses with light-sensitive lesions.

- If mud fever is secondary to an immune-mediated condition this will need to be treated and managed.

Figure 5: Cutimed® DebriClean monofilament debridement pad used for gentle and atraumatic debridement of skin, wound and superficial lesions.

Prevention & Prognosis

Prevention involves minimising exposure to wet and cold conditions, it is this constant exposure that has been linked to the causation of mud fever, this is supported by the fact that in yards where mud fever is a problem horses’ legs tend to be washed frequently, without adequate drying afterwards, leading to outbreaks, whereas yards that never or infrequently wash horses’ legs suffer with little problems. As an alternative to washing daily, it is recommended to allow mud to dry and brush it off

the following day. The rotation of paddocks to avoid poaching and the use of electric fences to block off particularly muddy areas, such as those around gateways, will aid in the prevention of mud fever.

Leaving lower legs unclipped was historically believed to protect the legs from infection, but this is not necessarily the case and hairier legs tend to take longer to dry increasing the time the limbs are left wet and hindering the early identification of lesions or skin damage. Waterproofing the lower limbs, particularly before turning out or exercising, is good practice and barrier creams or sprays, such as Cutimed® PROTECT, are effective at this. However, limbs must be clean and dry prior to application and apply in a thin layer to prevent ‘caking’ of the cream that could trap in microbes or worsen infection.

For cases of primary mud fever, the prognosis for full recovery is good, providing appropriate treatment is carried out in a timely manner, and rigorous ongoing management is instituted, and prevention methods are followed. However, if the condition is secondary to another disease process the resolution may not be as simple, and infection may not resolve until the secondary condition is controlled and treated leading to more serious systemic signs in the horse.

Conclusion

Mud fever is traditionally associated with mud coating the legs, however many out-wintered horses and ponies who live in muddy fields continue through the whole winter without developing any signs of mud fever. This leads us to believe that it is not merely the mud but instead consistent wetting and chilling of the skin leading to moisture-associated skin damage that increases the risk of bacteria penetrating deeper skin layers and replicating. This condition requires a multimodal approach and holistic assessment of the horse to ensure treatment is appropriate and to prevent the condition from worsening and consideration of the environmental factors to prevent re-occurrence.

References:

- British Horse Society, (2023) ‘Mud fever’ [Online] Available at: Mud Fever In Horses: Signs & Causes | The British Horse Society (bhs.org.uk)

- Moriello, K.A. (2022). ‘Dermatophilosis in animals’ Merek Manual [Online] Available at: Dermatophilosis in Animals – Integumentary System – MSD Veterinary Manual (msdvetmanual.com)